Quadrivium-Based Number Theory

as a Chess-Like Board Game

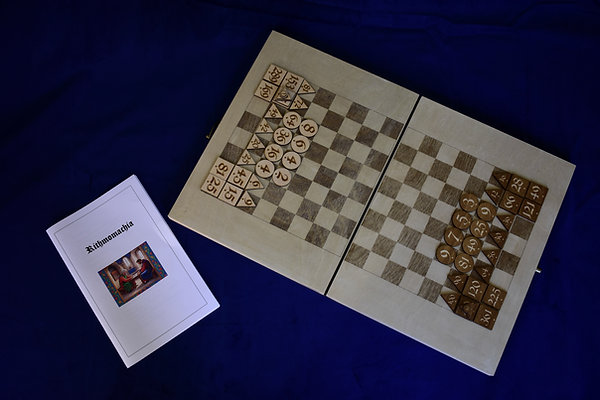

Rithmomachia (“Battle of Numbers”) was the most popular board game in medieval Europe. It combined the mechanics of chess with Boethian number theory and served dual educational and recreational purposes. It has now been revived.

The numerical values of the pieces were chosen for their arithmetic properties (odd and even) and proportional relations (especially the superparticular ratios studied in the texts of Nicomachus and Boethius).

Their movement ranges are determined by the piece's shape (and also a reference to circular, triangular, and square numbers studied in arithmetic).

Captures can only be performed by mathematical relations, such as the addition of attacking pieces or the multiplication of intervening spaces with the attacking piece's value.

Their are two victory tiers: one is a chosen condition based upon point value or a piece-count; the other is to place pieces on the opponents side in arithmetic, geometric, or harmonic proportion.

The Philosopher's Game:

"the most-popular game in Medieval Europe"

The game was, by legend, attributed to Pythagoras and his followers. Contemporary scholarship points to a 9th c. German monk named Arsilo, who having studied arithmetic within the quadrivium sought to make manifest its ideas into a game. The idea of using games to teach mathematics has advocacy as early as Plato, who himself claimed precedence from ancient Egypt.

The game took on a life of its own. It was greatly popular among the leisure classes who had studied the liberal arts. It held prominence even over chess, which had not yet bestowed to queen piece with the movement freedom it now holds, until the modern period.

It was referred to as "The Philosopher's Game" due to the disposition of those studying the liberal arts and enjoying rithmomachia with their studies. The player would not only have fun while learning some basic arithmetic (in our sense of the world) as well as arithmetic proper (number theory). In seeking to establish proportions on the opponent's side of the board, the player would be reflecting upon the harmony of numbers, the cosmos, and within the soul.

The game maintained popularity throughout the Renaissance period even as the study of the quadrivium began to decline. The early modern period produced several game manuals, which we aim to reproduce. A late a writer as Thomas More recommended its play in his Utopia - especially as it promoted better morals than games of chance involving dice. The game eventually fell into obscurity but has maintained interest from historians and game enthusiasts.

With the renewal of classical education and a reflection on the role of the quadrivium, this is an opportune moment for the revival of this great game.